Natural Resources - Human Rights

As Climate Change bites the dust,

West Africa seeks solutions

West Africa seeks solutions

By Robert Zougmoré

The weather in many parts of West Africa has a special element of capriciousness—strong sun followed by hard rains and sometimes fierce storms, followed by more strong sun.

Droughts are commonplace, and afterwards the soil is baked solid, impervious to rain and seeds alike.

As difficult as farming has been, lately it has been getting worse. Longer dry seasons. Stronger rainstorms. We have tolerated the weather for generations, but the change is becoming too drastic as our climate shifts.

Those of us watching saw irony in how industrialized countries competed to outdo each other in providing funds and humanitarian aid

As for today, farmers have no idea whether 2014 will bring another crisis like the dry spell of 2012, or whether the slightly more moderate weather of 2013 will continue.

West Africa does not hold the monopoly on unpredictable weather. We see it everywhere.

From cyclones and typhoons in the Pacific, polar ice melting, hurricanes in the Atlantic, drought and tornadoes in the U.S.—almost everyone, it seems, has to adapt. But West Africa, especially the Sahel, is known as one of the climate hotspots worldwide and merits special mention.

Delegates from all over the world gathered for two weeks in Warsaw towards the end of 2013 to discuss how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions so that climate change will not be so severe.

They have been negotiating a global agreement for years now, one that would limit the environmental impacts that humans induce, and to determine what if anything can

be done to help impoverished regions adapt to the new climates.

The negotiators failed once again; the answer from Warsaw seems to be that nothing

immediate can be done.

While a vague agreement on the parameters for the next round of negotiations was reached, there was no real progress achieved on climate change adaptation despite an obvious and ever-increasing need. And in agriculture, we saw no movement at all.

200 million trees

But fortunately in Niger, the farmers and policymakers are not sitting idly and waiting for global consensus. They, and many other developing countries who will be most impacted by the effects of climate change—especially on farming—are making impressive changes to prepare for an uncertain future.

Nigeriens, for example, have been adapting by regrowing trees whose stumps lay dormant in the soil—trees that had been previously cleared for farmland. This process is known as farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR).

Adding trees alongside the crops provides shelter from the elements, augments the amount of organic matter and nitrogen in the soil, adds fruit and firewood to a farmer's yields, and even raises groundwater levels.

The technique has spread by word of mouth throughout the country over the past three decades, and analysts estimate that farmers in Niger have grown 200 million trees and rehabilitated five million hectares of degraded land.

Farmers in Niger are also working to harvest the rainfall that reaches their land.

Small stone walls 20 to 30cm tall—known as bunds—helps slow down the runoff from farm fields so that the sun-hardened ground can absorb more. The bunds also prevent soil and silt from washing away.

Zai pits—shallow bowls dug into the ground and filled with compost or manure—also

help capture the rain and channel it into the soil.

As effective as these additions to the agricultural landscape have been, more is needed. But here too, Niger has not sat idle.

The government has prepared a National Adaptation Plan of Action, a strategy document that looks at how agriculture can adapt to expected climate change impacts.

Concrete initiatives that are being implemented include broadcasting weather data and forecasts more widely, establishing food banks to help both people and livestock survive through lean times, and promoting livestock and crops that are better adapted to the expected macroclimate.

In 2006, Niger was one of the first countries in West Africa to produce an adaptation plan; now almost all West African countries and many others around the world have prepared their own strategies.

Planning for climate change is only the first step in adapting, of course. Many developing countries need funds so that these strategies can be implemented.

Humanitarian aid competition

And that brings us back to the climate change talks. The failure of the Warsaw negotiations was apparent almost as soon as it started, despite a tearful plea by a delegate from the Philippines after the latest super storm cut a swathe of near-total destruction through his country.

Those of us watching saw irony in how industrialized countries competed to outdo each other in providing funds and humanitarian aid to the Philippines.

The same countries in Warsaw ignored the pleas of the Philippine delegation to take action on emissions and adaptation funding. It was as if the climate change negotiations had nothing to do with the unruly climate in the Pacific.

Niger's government, like those of other West African nations, is turning elsewhere—bilateral funds, public-private partnerships, and international institutions like the World Bank—to fund its climate adaptation plan.

And by partnering with initiatives like the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the government aims to grow participation in community-based climate-smart agriculture efforts.

But while these initiatives lay the critical foundation for climate-change adaptation, what's missing is the global political push that can kick start large-scale research and investment, especially in the agriculture sector.

The lack of progress at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—the official name for these endless negotiations—is the one part of global warming that has remained static, as negotiators have not moved from positions that are literally decades old.

It is now 2014, a new year and past time for everyone to put aside self-interest.

The weather is changing and it will only get worse, therefore let us all also change our respective behaviors!

Robert Zougmoré is the West Africa Program Leader for the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). He is based at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in Bamako, Mali.

Read the original article on TheAfricaReport.com : As Climate Change bites the dust, West Africa seeks solutions

www.theafricareport.com/North-Africa/as-climate-change-bites-the-dust-west-africa-seeks-solutions.html

Droughts are commonplace, and afterwards the soil is baked solid, impervious to rain and seeds alike.

As difficult as farming has been, lately it has been getting worse. Longer dry seasons. Stronger rainstorms. We have tolerated the weather for generations, but the change is becoming too drastic as our climate shifts.

Those of us watching saw irony in how industrialized countries competed to outdo each other in providing funds and humanitarian aid

As for today, farmers have no idea whether 2014 will bring another crisis like the dry spell of 2012, or whether the slightly more moderate weather of 2013 will continue.

West Africa does not hold the monopoly on unpredictable weather. We see it everywhere.

From cyclones and typhoons in the Pacific, polar ice melting, hurricanes in the Atlantic, drought and tornadoes in the U.S.—almost everyone, it seems, has to adapt. But West Africa, especially the Sahel, is known as one of the climate hotspots worldwide and merits special mention.

Delegates from all over the world gathered for two weeks in Warsaw towards the end of 2013 to discuss how to reduce greenhouse gas emissions so that climate change will not be so severe.

They have been negotiating a global agreement for years now, one that would limit the environmental impacts that humans induce, and to determine what if anything can

be done to help impoverished regions adapt to the new climates.

The negotiators failed once again; the answer from Warsaw seems to be that nothing

immediate can be done.

While a vague agreement on the parameters for the next round of negotiations was reached, there was no real progress achieved on climate change adaptation despite an obvious and ever-increasing need. And in agriculture, we saw no movement at all.

200 million trees

But fortunately in Niger, the farmers and policymakers are not sitting idly and waiting for global consensus. They, and many other developing countries who will be most impacted by the effects of climate change—especially on farming—are making impressive changes to prepare for an uncertain future.

Nigeriens, for example, have been adapting by regrowing trees whose stumps lay dormant in the soil—trees that had been previously cleared for farmland. This process is known as farmer-managed natural regeneration (FMNR).

Adding trees alongside the crops provides shelter from the elements, augments the amount of organic matter and nitrogen in the soil, adds fruit and firewood to a farmer's yields, and even raises groundwater levels.

The technique has spread by word of mouth throughout the country over the past three decades, and analysts estimate that farmers in Niger have grown 200 million trees and rehabilitated five million hectares of degraded land.

Farmers in Niger are also working to harvest the rainfall that reaches their land.

Small stone walls 20 to 30cm tall—known as bunds—helps slow down the runoff from farm fields so that the sun-hardened ground can absorb more. The bunds also prevent soil and silt from washing away.

Zai pits—shallow bowls dug into the ground and filled with compost or manure—also

help capture the rain and channel it into the soil.

As effective as these additions to the agricultural landscape have been, more is needed. But here too, Niger has not sat idle.

The government has prepared a National Adaptation Plan of Action, a strategy document that looks at how agriculture can adapt to expected climate change impacts.

Concrete initiatives that are being implemented include broadcasting weather data and forecasts more widely, establishing food banks to help both people and livestock survive through lean times, and promoting livestock and crops that are better adapted to the expected macroclimate.

In 2006, Niger was one of the first countries in West Africa to produce an adaptation plan; now almost all West African countries and many others around the world have prepared their own strategies.

Planning for climate change is only the first step in adapting, of course. Many developing countries need funds so that these strategies can be implemented.

Humanitarian aid competition

And that brings us back to the climate change talks. The failure of the Warsaw negotiations was apparent almost as soon as it started, despite a tearful plea by a delegate from the Philippines after the latest super storm cut a swathe of near-total destruction through his country.

Those of us watching saw irony in how industrialized countries competed to outdo each other in providing funds and humanitarian aid to the Philippines.

The same countries in Warsaw ignored the pleas of the Philippine delegation to take action on emissions and adaptation funding. It was as if the climate change negotiations had nothing to do with the unruly climate in the Pacific.

Niger's government, like those of other West African nations, is turning elsewhere—bilateral funds, public-private partnerships, and international institutions like the World Bank—to fund its climate adaptation plan.

And by partnering with initiatives like the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), the government aims to grow participation in community-based climate-smart agriculture efforts.

But while these initiatives lay the critical foundation for climate-change adaptation, what's missing is the global political push that can kick start large-scale research and investment, especially in the agriculture sector.

The lack of progress at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—the official name for these endless negotiations—is the one part of global warming that has remained static, as negotiators have not moved from positions that are literally decades old.

It is now 2014, a new year and past time for everyone to put aside self-interest.

The weather is changing and it will only get worse, therefore let us all also change our respective behaviors!

Robert Zougmoré is the West Africa Program Leader for the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). He is based at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) in Bamako, Mali.

Read the original article on TheAfricaReport.com : As Climate Change bites the dust, West Africa seeks solutions

www.theafricareport.com/North-Africa/as-climate-change-bites-the-dust-west-africa-seeks-solutions.html

Agricultural Justice

Thanks to www.FairWorldProject.Org, here are resources for the world's farmers . The contacts listed below can

be reached through Fair World Project. Following the contacts, there is an article by one of the people listed below, Karen

Hansen-Kuhn on corporate monopolization of the world's land. The title is "Land Grab."

Dana Geffner

Executive Director

Fair World Project

www.fairworldproject.org

Executive Director

Fair World Project

www.fairworldproject.org

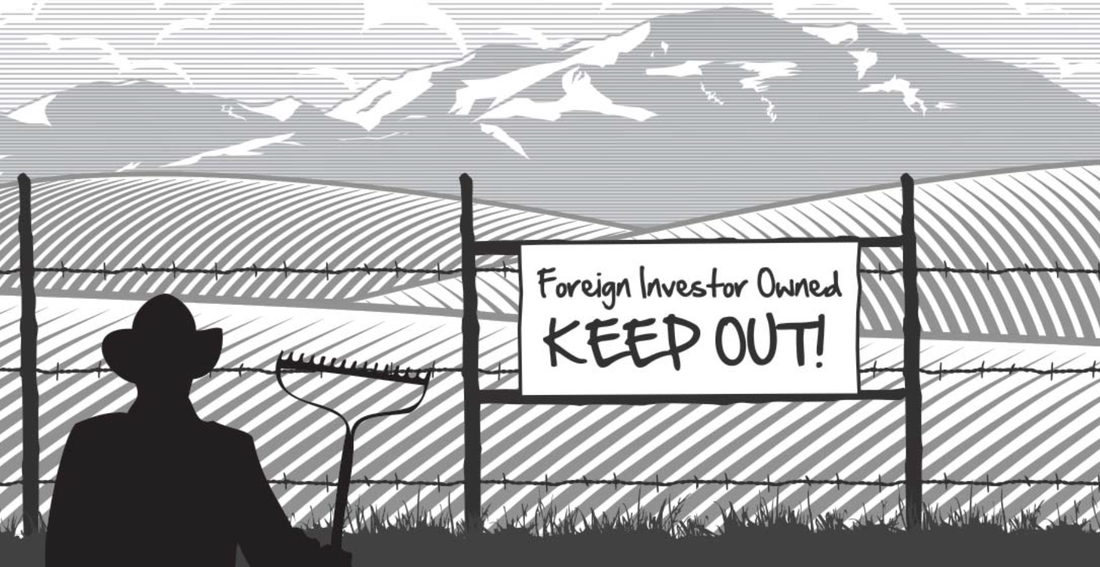

Land Grab

Contributing Writer - Karen Hansen-Kuhn

Conflicts between small-scale farmers or farmworkers and foreign investors have been raging for decades, if not centuries. The pace and scope of land grabs over the last few years, however, is new. In the decades leading up to the 2008 food and financial crisis, free trade and investment agreements created the legal conditions for land grabs, but low commodity prices depressed the demand for farmland in developing countries. When food prices spiked, there was a rush of new investments by corporations, financial investors and sovereign wealth funds, many of which were not directly involved in food production.

Millions of hectares have since been leased or sold, often without the knowledge or consent of the communities who will be most affected by those decisions. The Land Matrix (www.landmatrix.org), a new collaborative Web tool, has documented more than 1,000 cases involving nearly thirty-three million hectares. The site tracks deals (involving 200 or more hectares) made since 2000 that involve the conversion of land from smallholder production or community use in low- and middle-income countries. Other estimates have ranged as high as 100 million hectares.

There are several overlapping challenges here. First, land tenure laws are unclear in many countries. Under the customary laws prevalent in many African countries, for example, community elders might sign off on land deals without consulting the people farming those lands. Or, decisions can be made far up the chain in remote bureaucracies. In any case, the idea that these lands are somehow vacant blank slates just waiting for new investments is usually flat wrong, and expanding industrial agricultural production (often for export) in delicate ecosystems (where farmers may practice shifting cultivation) can have devastating social and environmental impacts.

Who are the land grabbers? Some are national governments lacking capacity for local production and feeling burned by recent failures in global markets. But much of the grabbing is being done by banks, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and hedge funds looking for the next new target for innovative investments. The rising demand for biofuels also creates new incentives for investors interested in exploiting this huge new market. The investment fund TIAA-CREF, for example, launched a new fund for investments in farmland. In that case, and with similar investments by pension funds and hedge funds, the fi rm purchases land outright or leases it for decades into the future. They are assuming that land prices will continue to rise as demand for food production increases, and that assumption itself, along with the volume of new investments, puts upward pressure on land prices and therefore even greater pressure on farmers around the world.

In tracking land grabs, the Land Matrix came up with some surprising conclusions. It turns out the land grabbers often bite off more than they can chew, buying or leasing hundreds of thousands of hectares, when it turns out they can only cultivate about 5% of that amount. In many cases, the deals shrink or collapse, but in others the foreign investors simply hold on to the property rights, biding their time for a better deal down the road.

The solutions, like the problem, are complex. Campaigns to challenge specific land grabs are emerging every day, led by such groups as the Oakland Institute. Campaigns and stunts in Europe, led by the World Development Movement, convinced at least a few investment firms to divest from land. At the international level, eff orts are underway to move the UN Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Land Tenure from an innovative tool of soft law to something real and enforceable. All of these efforts, along with others challenging free trade and investment agreements (like the Trans-Pacific Partnership) that are driving these bad deals, are needed to help keep land in the hands of farmers around the world.

For more information on the causes of land grabs, see Land Grabs and Fragile Food Systems: The Role of Globalization by Sophia Murphy.

To download the full publication of FOR A BETTER WORLD by www.fairworldproject.org ,

please click the link -

http://fairworldproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Fair_World_Project_Publication_Fall_issue_7.pdf

Contributing Writer - Karen Hansen-Kuhn

Conflicts between small-scale farmers or farmworkers and foreign investors have been raging for decades, if not centuries. The pace and scope of land grabs over the last few years, however, is new. In the decades leading up to the 2008 food and financial crisis, free trade and investment agreements created the legal conditions for land grabs, but low commodity prices depressed the demand for farmland in developing countries. When food prices spiked, there was a rush of new investments by corporations, financial investors and sovereign wealth funds, many of which were not directly involved in food production.

Millions of hectares have since been leased or sold, often without the knowledge or consent of the communities who will be most affected by those decisions. The Land Matrix (www.landmatrix.org), a new collaborative Web tool, has documented more than 1,000 cases involving nearly thirty-three million hectares. The site tracks deals (involving 200 or more hectares) made since 2000 that involve the conversion of land from smallholder production or community use in low- and middle-income countries. Other estimates have ranged as high as 100 million hectares.

There are several overlapping challenges here. First, land tenure laws are unclear in many countries. Under the customary laws prevalent in many African countries, for example, community elders might sign off on land deals without consulting the people farming those lands. Or, decisions can be made far up the chain in remote bureaucracies. In any case, the idea that these lands are somehow vacant blank slates just waiting for new investments is usually flat wrong, and expanding industrial agricultural production (often for export) in delicate ecosystems (where farmers may practice shifting cultivation) can have devastating social and environmental impacts.

Who are the land grabbers? Some are national governments lacking capacity for local production and feeling burned by recent failures in global markets. But much of the grabbing is being done by banks, sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and hedge funds looking for the next new target for innovative investments. The rising demand for biofuels also creates new incentives for investors interested in exploiting this huge new market. The investment fund TIAA-CREF, for example, launched a new fund for investments in farmland. In that case, and with similar investments by pension funds and hedge funds, the fi rm purchases land outright or leases it for decades into the future. They are assuming that land prices will continue to rise as demand for food production increases, and that assumption itself, along with the volume of new investments, puts upward pressure on land prices and therefore even greater pressure on farmers around the world.

In tracking land grabs, the Land Matrix came up with some surprising conclusions. It turns out the land grabbers often bite off more than they can chew, buying or leasing hundreds of thousands of hectares, when it turns out they can only cultivate about 5% of that amount. In many cases, the deals shrink or collapse, but in others the foreign investors simply hold on to the property rights, biding their time for a better deal down the road.

The solutions, like the problem, are complex. Campaigns to challenge specific land grabs are emerging every day, led by such groups as the Oakland Institute. Campaigns and stunts in Europe, led by the World Development Movement, convinced at least a few investment firms to divest from land. At the international level, eff orts are underway to move the UN Voluntary Guidelines on the Responsible Governance of Land Tenure from an innovative tool of soft law to something real and enforceable. All of these efforts, along with others challenging free trade and investment agreements (like the Trans-Pacific Partnership) that are driving these bad deals, are needed to help keep land in the hands of farmers around the world.

For more information on the causes of land grabs, see Land Grabs and Fragile Food Systems: The Role of Globalization by Sophia Murphy.

To download the full publication of FOR A BETTER WORLD by www.fairworldproject.org ,

please click the link -

http://fairworldproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Fair_World_Project_Publication_Fall_issue_7.pdf

VOICE FROM THE SOUTH

VANDANA SHIVA (India)

CO-OPTED

The Americanisation of Indian agriculture will lead to more corporate dictatorship and violence.

Terrorism and agriculture were among the issues raised in the Joint India - US tatement issued in July during Prime Minister Man Mohan Singh’s meeting with President Bush. As the statement declares, the two leaders resolved:

• to create an international environment conducive to promotion of democratic values, and to strengthen democratic practices in societies which wish to become open and pluralistic; and

• to combat terrorism relentlessly.

The leaders also agreed, in a Science and Technology Co-operation Agreement, to:

• launch a US–India knowledge initiative on agriculture focused on promoting teaching, research, service and commercial linkages. The agreement made it clear that teaching and research would focus on biotechnology or genetic engineering, also often referred to as the Second Green Revolution. The agreement cites the Green Revolution of the 1960s as the beginning of US–India co-operation in India. However, to assess the impact of the new agreement we need an honest appraisal of the impact of the first Green Revolution.

When we became independent, our agriculture was in crisis due to neglect and exploitation. The Agriculture Minister prioritised the repair of nature’s hydrological and nutritional cycles: the principles followed in sustainable, ecological farming.

However, while Indian scientists and policy-makers were working out self-reliant and ecological alternatives for the regeneration of agriculture in India, another vision of agricultural development was taking shape in US foundations and aid agencies. This vision was based not on co-operation with nature, but on its conquest. It was based not on the intensification of nature’s processes, but on the intensification of credit and purchased inputs like chemical fertilisers and pesticides. It was based not on self-reliance, but on dependence. It was based not on diversity, but on uniformity.

Advisers and experts came from the US to shift India’s agricultural research and agricultural policy from an indigenous and ecological model to an exogenous and high input one, finding, of course, partners in sections of the elite, because the new model suited their political priorities and interests.

The occurrence of drought in1966 caused a severe drop in food production in India, and an unprecedented increase in food grain supply from the US was used to set new policy conditions on India. The US President, Lyndon Johnson, put wheat supplies on a short tether. He refused to commit food aid beyond one month in advance until an agreement to adopt the Green Revolution package was signed between the Indian agriculture minister and the US secretary of agriculture.

The Green Revolution, awarded a Nobel Prize for Peace in 1970, has contributed to two social and environmental disasters in India. One was the extremist movement and terrorism in Punjab, which led to the military assault on the Golden Temple and finally the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984. The other was the gas leak from the Union Carbide pesticides plant in Bhopal, which killed 3,000 people on one tragic night in December 1984. In the two decades since that disaster, 30,000 people have died in Bhopal as a result of the leak of these toxic gases. The Punjab violence also took the lives of 30,000 people in the years following 1984.

Why did a ‘Revolution’ awarded a Nobel Peace Prize lead to so much violence? The Green Revolution came with a promise of peace, but its crude linearity (Technology = Prosperity = Peace) failed. The reason for this failure was that the technologies of the Green Revolution, like technologies of war, leave nature and society impoverished. To expect prosperity to grow out of violent technologies that destroy the earth, erode biodiversity, deplete and pollute water and leave peasants indebted and in ruins was a false assumption made during the launch of the Green Revolution. This false assumption is being repeated in the launch of the Second Green Revolution based on biotechnology and genetic engineering, which are at the core of the US–India agreement.

The‘terrorism’ and ‘extremism’ in Punjab were born out of the experience of the injustice of the Green Revolution as a development model, which centralised power and appropriated resources and earth from the people. In the words of the Gurmata from the All Sikh Convention in April 1986, “If the hard-earned income of the people or the natural resources of any nation or the region are forcibly plundered; if the goods produced by them are paid for at arbitrarily determined prices while the goods bought are sold at higher prices and if, in order to carry this process of economic exploitation to its logical conclusion, the human rights of a nation, region or people are lost then the people will be like the Sikhs today —shackled by the chains of slavery.”

The people of Punjab were clearly not experiencing the Green Revolution as a source of prosperity and freedom. For them it was slavery. The Green Revolution, the social and ecological impacts it had, and the responses it created among an angry and disillusioned peasantry have many lessons for our times, both for understanding the roots of terrorism and for searching for solutions to violence.

These are connections our leaders fail to make. The more they fight terrorism, the more they create it with their policies that create economic insecurity. The more they talk democracy, the more they destroy freedom by imposing trade rules and policies that deny people freedom and work against farmers and citizens. The Agreement on Agriculture of the World Trade Organization was drafted by a Cargill official. The Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights Agreement was drafted by a group of US corporations including Monsanto. Monsanto’s seed monopolies have already pushed thousands of farmers in India to suicide. Promoting commerce for Monsanto and Cargill through the US–India Agreement on Agriculture will kill more farmers and ultimately destroy India’s food security, sovereignty and democracy, fuelling more terrorism and extremism.

The Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement between the US and India establishes intellectual property protocols of research, bypassing consultation with Indian scientists and the Indian public, who have been resisting the US-style Intellectual Property Rights regimes (which force countries to patent life, and create monopolies on seeds, medicine and software). For us, these agreements are instruments of corporate dictatorship; they are not instruments of democracy. And as a dictatorship, they will fuel more anger, more discontent, more frustration.

Terrorism is a child of economically unjust and anti-democratic policies, as became clear in Punjab in India and Oklahoma in the US. As Joel Dyer says in Harvest of Rage, an investigation into the Oklahoma bombing and its roots in the US farm crisis, farmers losing their farms and livelihoods are victims of long-term stress. If they are not helped, they become violent. If they blame themselves, they direct violence inwards and commit suicide. If they blame others, they turn their violence outwards. This is the violence of terrorism and extremism. The only lasting solution to dealing with terror is to increase people’s freedom and security by protecting their livelihoods, their cultures, their rights to resources, and their democratic choices in how their society and lives are organised.

The US–India Agreement on Agriculture and Science and Technology will do the opposite. It will breed more insecurity and erode people’s capacity to make choices. It will therefore fail in its two prime objectives of promoting democracy and ending terrorism.

Co-opted featured in Resurgence issue 233, November/December 2005.

This article is reprinted courtesy of Resurgence magazine – at the heart of earth, art and spirit. To buy Resurgence, read further articles online or find out about The Resurgence Trust, visit: www.resurgence.org

All rights to this article are reserved to Resurgence, if you wish to republish or make use of this work you must contact the copyright owner to obtain permission.

Terrorism and agriculture were among the issues raised in the Joint India - US tatement issued in July during Prime Minister Man Mohan Singh’s meeting with President Bush. As the statement declares, the two leaders resolved:

• to create an international environment conducive to promotion of democratic values, and to strengthen democratic practices in societies which wish to become open and pluralistic; and

• to combat terrorism relentlessly.

The leaders also agreed, in a Science and Technology Co-operation Agreement, to:

• launch a US–India knowledge initiative on agriculture focused on promoting teaching, research, service and commercial linkages. The agreement made it clear that teaching and research would focus on biotechnology or genetic engineering, also often referred to as the Second Green Revolution. The agreement cites the Green Revolution of the 1960s as the beginning of US–India co-operation in India. However, to assess the impact of the new agreement we need an honest appraisal of the impact of the first Green Revolution.

When we became independent, our agriculture was in crisis due to neglect and exploitation. The Agriculture Minister prioritised the repair of nature’s hydrological and nutritional cycles: the principles followed in sustainable, ecological farming.

However, while Indian scientists and policy-makers were working out self-reliant and ecological alternatives for the regeneration of agriculture in India, another vision of agricultural development was taking shape in US foundations and aid agencies. This vision was based not on co-operation with nature, but on its conquest. It was based not on the intensification of nature’s processes, but on the intensification of credit and purchased inputs like chemical fertilisers and pesticides. It was based not on self-reliance, but on dependence. It was based not on diversity, but on uniformity.

Advisers and experts came from the US to shift India’s agricultural research and agricultural policy from an indigenous and ecological model to an exogenous and high input one, finding, of course, partners in sections of the elite, because the new model suited their political priorities and interests.

The occurrence of drought in1966 caused a severe drop in food production in India, and an unprecedented increase in food grain supply from the US was used to set new policy conditions on India. The US President, Lyndon Johnson, put wheat supplies on a short tether. He refused to commit food aid beyond one month in advance until an agreement to adopt the Green Revolution package was signed between the Indian agriculture minister and the US secretary of agriculture.

The Green Revolution, awarded a Nobel Prize for Peace in 1970, has contributed to two social and environmental disasters in India. One was the extremist movement and terrorism in Punjab, which led to the military assault on the Golden Temple and finally the assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984. The other was the gas leak from the Union Carbide pesticides plant in Bhopal, which killed 3,000 people on one tragic night in December 1984. In the two decades since that disaster, 30,000 people have died in Bhopal as a result of the leak of these toxic gases. The Punjab violence also took the lives of 30,000 people in the years following 1984.

Why did a ‘Revolution’ awarded a Nobel Peace Prize lead to so much violence? The Green Revolution came with a promise of peace, but its crude linearity (Technology = Prosperity = Peace) failed. The reason for this failure was that the technologies of the Green Revolution, like technologies of war, leave nature and society impoverished. To expect prosperity to grow out of violent technologies that destroy the earth, erode biodiversity, deplete and pollute water and leave peasants indebted and in ruins was a false assumption made during the launch of the Green Revolution. This false assumption is being repeated in the launch of the Second Green Revolution based on biotechnology and genetic engineering, which are at the core of the US–India agreement.

The‘terrorism’ and ‘extremism’ in Punjab were born out of the experience of the injustice of the Green Revolution as a development model, which centralised power and appropriated resources and earth from the people. In the words of the Gurmata from the All Sikh Convention in April 1986, “If the hard-earned income of the people or the natural resources of any nation or the region are forcibly plundered; if the goods produced by them are paid for at arbitrarily determined prices while the goods bought are sold at higher prices and if, in order to carry this process of economic exploitation to its logical conclusion, the human rights of a nation, region or people are lost then the people will be like the Sikhs today —shackled by the chains of slavery.”

The people of Punjab were clearly not experiencing the Green Revolution as a source of prosperity and freedom. For them it was slavery. The Green Revolution, the social and ecological impacts it had, and the responses it created among an angry and disillusioned peasantry have many lessons for our times, both for understanding the roots of terrorism and for searching for solutions to violence.

These are connections our leaders fail to make. The more they fight terrorism, the more they create it with their policies that create economic insecurity. The more they talk democracy, the more they destroy freedom by imposing trade rules and policies that deny people freedom and work against farmers and citizens. The Agreement on Agriculture of the World Trade Organization was drafted by a Cargill official. The Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights Agreement was drafted by a group of US corporations including Monsanto. Monsanto’s seed monopolies have already pushed thousands of farmers in India to suicide. Promoting commerce for Monsanto and Cargill through the US–India Agreement on Agriculture will kill more farmers and ultimately destroy India’s food security, sovereignty and democracy, fuelling more terrorism and extremism.

The Science and Technology Cooperation Agreement between the US and India establishes intellectual property protocols of research, bypassing consultation with Indian scientists and the Indian public, who have been resisting the US-style Intellectual Property Rights regimes (which force countries to patent life, and create monopolies on seeds, medicine and software). For us, these agreements are instruments of corporate dictatorship; they are not instruments of democracy. And as a dictatorship, they will fuel more anger, more discontent, more frustration.

Terrorism is a child of economically unjust and anti-democratic policies, as became clear in Punjab in India and Oklahoma in the US. As Joel Dyer says in Harvest of Rage, an investigation into the Oklahoma bombing and its roots in the US farm crisis, farmers losing their farms and livelihoods are victims of long-term stress. If they are not helped, they become violent. If they blame themselves, they direct violence inwards and commit suicide. If they blame others, they turn their violence outwards. This is the violence of terrorism and extremism. The only lasting solution to dealing with terror is to increase people’s freedom and security by protecting their livelihoods, their cultures, their rights to resources, and their democratic choices in how their society and lives are organised.

The US–India Agreement on Agriculture and Science and Technology will do the opposite. It will breed more insecurity and erode people’s capacity to make choices. It will therefore fail in its two prime objectives of promoting democracy and ending terrorism.

Co-opted featured in Resurgence issue 233, November/December 2005.

This article is reprinted courtesy of Resurgence magazine – at the heart of earth, art and spirit. To buy Resurgence, read further articles online or find out about The Resurgence Trust, visit: www.resurgence.org

All rights to this article are reserved to Resurgence, if you wish to republish or make use of this work you must contact the copyright owner to obtain permission.

Embrace Foundation is a non-profit,

educational foundation set up to create

better understanding between people of

different religions, cultures, traditions and

world philosophies.

Embrace Foundation works to bring leaders

and scholars of world-wide religions, cultures

and philosophies together by sponsoring

forums, seminars, lectures and developing

an international exchange program.

Embrace Foundation is particularly

concerned with reaching the world public

through the media.

Purpose

Donations

Embrace Foundation is an all volunteer

organization. All donations go directly to

programs.

Embrace Foundation does not and has

never given permission to any outside

organization to solicit or receive

contributions on our behalf.

All donations should be made to Embrace

Foundation only via Paypal or by mail. All

donations are tax deductible. A receipt will

be emailed to you. Please click on the Pay

Pal link below to Donate.

Travel As An Interfaith Act

Embrace encourages all who can do so, to

learn about other traditions and cultures by

traveling as “Grassroots Diplomats.” We

hope that people every where become life

long students of our world-wide humanity.

“ In every man there is something wherein I

may learn of him, and in that I am his pupil.”

R.W.Emerson

Embrace Humanity

Great Visions - TV

Guests are: Swami Satchidananda &

the Rt. Reverend Dean Parks Morton

Embrace Archives

Limited Editions Gallery

Umrah - Jordan

Embrace Sacred Places

Monastery of Bahira - Syria

Embrace Foundation Universal

Monk Reading - Ethiopia

Thank you for making a donation.

Who Owns Agricultural Land in Ukraine?

By:

Elizabeth Fraser

The fate of Ukraine’s agricultural sector is on shaky ground. Last year, the Oakland Institute reported that over 1.6 million hectares (ha) of land in Ukraine are now under the control of foreign based corporations. Further research has allowed for the identification of additional foreign investments. Some estimates now bring the total of Ukrainian farmland controlled by foreign companies to over 2.2 million ha;1 however, research has also identified important grey areas around land tenure in the country, and who actually controls land in Ukraine today is difficult to ascertain.

The companies and shareholders behind foreign land acquisitions in Ukraine span many different parts of the world. The Danish "Trigon Agri," for example, holds over 52,000 ha. Trigon was established in 2006 using start-up capital from Finnish "high net worth individuals." The company is traded in Stockholm (NASDAQ), and its largest shareholders include: JPM Chase (UK, 9.5 percent); Swedbank (Sweden, 9.4 percent); UB Securities (Finland, 7.9 percent); Euroclear Bank (Belgium, 6.6 percent); and JP Morgan Clearing Corp (USA, 6.2 percent).

The United Farmers Holding Company, which is owned by a group of Saudi Arabian investors, controls some 33,000 ha of Ukrainian farmland through Continental Farmers Group PLC. AgroGeneration, which holds 120,000 ha of Ukrainian farmland, is incorporated in France, with over 62 percent of its shares managed by SigmaBleyzer, a Texas-based investment company.

US pension fund NCH Capital holds 450,000 ha. The company began in 1993 and boasts being some of the earliest western investors in Ukraine after the break-up of the Soviet Union. Over the past decade, the company has systematically leased out small parcels of agricultural land (around two to six hectares in size) across Ukraine, aggregating these into large-scale farms that now operate industrially. According to NCH Capital’s General Partner, George Rohr, the leases give the company the right to buy the currently-leased farmland once the moratorium on the sale of land in Ukraine is lifted.

Another subset of companies have Ukrainian leadership, often a mix of domestic and foreign investment, and may be incorporated in tax havens like Cyprus, Austria, and Luxembourg. Some of them are also led by Ukrainian oligarchs. For instance, UkrLandFarming controls the country's largest land-bank, totalling 654,000 ha of land. 95 percent of the shares of UkrLandFarming are owned by multi-millionaire Oleg Bakhmatyuk with the remaining five percent having been recently sold to Cargill. Similarly, Yuriy Kosiuk, Ukraine's fifth richest man, is the CEO of MHP, one of the country's largest agricultural companies, which holds over 360,000 ha of farmland.

With the onset of the political crisis, several of these mostly Ukrainian-based companies have descended into crisis themselves. One example is Cyprus-incorporated Mriya Agro Holding, which holds a land-bank of close to 300,000 ha. In 2014, the company’s website (which is no longer available online) indicated that 80 percent of the shares of Mriya Agro Holding are/were owned by the Guta family (Ukrainian), who hold primary leadership positions in the company. The remaining 20 percent are/were listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange.

According to news sources, in summer 2014 the company defaulted on its payments for two large Eurobonds, putting its future into question. The company first enlisted the support of US-based Blackstone Group and Ukrainian-based Dragon Capital, both of whom withdrew support after only one month; and later, the international auditing and financial service firm, Deloitte. An international bondholder committee was struck, comprised of several US and UK-based investment groups (including CarVal Investors – Cargill’s investment arm), which together own over 50 percent of the debt owed on Mriya’s 2018 Eurobonds and 15 percent of the 2016 Eurobonds. The future of this firm is unclear with some sources suggesting a risk of bankruptcy.

Other Ukrainian-owned companies incorporated in tax havens are also experiencing difficulties. Sintal Agriculture Public Ltd (based in Cyprus, traded on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange as of 2008, and holding almost 150,000 ha of land) ceased trading in shares on January 29, 2014 "until further notice" after bankruptcy proceedings were initiated against the company. In 2013, its website (now also defunct) indicated that 36.3 percent of the company was free floating shares.

The potential bankruptcy of these corporations, and the involvement of Western investors in the crisis management, raises questions about the fate of the agricultural land they hold. At this time, it is not clear how control over the agricultural lands in question will be addressed and what the role of foreign companies and funds who have invested in these companies will be. However, if things progress in a similar way to neighboring Romania, foreign control of this land could transpire.

Romania has a similar story of dissolving collectivized farms, giving land titles to collective farm workers, and imposing a moratorium on the sale of agricultural land. Loopholes in the country’s national legislation have created opportunities for foreign control of land via bankruptcy proceedings. As documented by Judith Bouniol, the bankruptcy of national agribusinesses has provided a gateway for foreign control of Romania’s farmland.

It is far from clear if the same scenario could take place in Ukraine. However, this lesson from Romania emphasizes the importance of keeping close watch on these agricultural land deals. In addition, the murky situation around land ownership in Ukraine raises many questions. Perhaps the most important is whether the growing concentration of Ukrainian land in the hands of a few oligarchs and foreign corporations can benefit the country, its people, and its economy.

--

1 Two land investment databases were accessed over the past year: the Land Matrix accessed in July 2014 and April 2015, and GRAIN’s 2012 data set on land investments worldwide. Taken individually, these databases suggest foreign land acquisitions of between 997,000 ha to 1.7M ha. When consolidated, individual deals reported by these databases represent over 2.2M ha of land in Ukraine.

See Article - http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/who-owns-agricultural-land-ukraine

Article from -

The Oakland Institute, P.O. Box 18978, Oakland, CA 94619 - 510-474-5251

info@oaklandinstitute.org

Shafted: The winners and losers of Ukraine’s austerity agenda

By:

Elizabeth Fraser

On March 2, 2015, the Ukrainian government passed amendments to its 2015 budget that will cripple the economic well being of most Ukrainians, but satisfy the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At the cost of their pensions, tax increases, sky-rocketing energy bills, and a re-organized banking sector, Ukrainians are now poised to get an IMF-led bailout of up to $40 billion. These austerity measures will have a huge adverse impact – with inflation soaring, many citizens of Ukraine already face dwindling financial reserves. Increases in taxes, energy bills, and lost pensions, are enough to throw any family into financial turmoil. These reforms also have vast implications for Ukraine’s agricultural sector.

The IMF and World Bank have been pushing for Ukraine to lift its moratorium on the sale of farmland for some time. In early March, Heinz Strubenhoff, the agribusiness investment manager for the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation in Ukraine, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that “it’s time to think about privatization,” and urged Ukrainians to “prepare everything to allow for farm land sales (to foreign and domestic investors).” Given the power that the IMF and World Bank hold over Ukraine right now, their wishes may finally come true.

Land is a precious commodity in Ukraine. The country is known as Europe’s bread basket, and holds some of the world’s most fertile soils. In 2001, Ukraine passed a Land Code, providing Ukrainians who had previously been part of collectivized farms with titles to approximately four hectares of land each. Since then, the majority of farmland has been in the hands of either smallholder farmers or the government, with a country-wide moratorium on its sale.

See rest of the article -

http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/shafted-winners-and-losers-ukraine%E2%80%99s-austerity-agenda

By:

Elizabeth Fraser

The fate of Ukraine’s agricultural sector is on shaky ground. Last year, the Oakland Institute reported that over 1.6 million hectares (ha) of land in Ukraine are now under the control of foreign based corporations. Further research has allowed for the identification of additional foreign investments. Some estimates now bring the total of Ukrainian farmland controlled by foreign companies to over 2.2 million ha;1 however, research has also identified important grey areas around land tenure in the country, and who actually controls land in Ukraine today is difficult to ascertain.

The companies and shareholders behind foreign land acquisitions in Ukraine span many different parts of the world. The Danish "Trigon Agri," for example, holds over 52,000 ha. Trigon was established in 2006 using start-up capital from Finnish "high net worth individuals." The company is traded in Stockholm (NASDAQ), and its largest shareholders include: JPM Chase (UK, 9.5 percent); Swedbank (Sweden, 9.4 percent); UB Securities (Finland, 7.9 percent); Euroclear Bank (Belgium, 6.6 percent); and JP Morgan Clearing Corp (USA, 6.2 percent).

The United Farmers Holding Company, which is owned by a group of Saudi Arabian investors, controls some 33,000 ha of Ukrainian farmland through Continental Farmers Group PLC. AgroGeneration, which holds 120,000 ha of Ukrainian farmland, is incorporated in France, with over 62 percent of its shares managed by SigmaBleyzer, a Texas-based investment company.

US pension fund NCH Capital holds 450,000 ha. The company began in 1993 and boasts being some of the earliest western investors in Ukraine after the break-up of the Soviet Union. Over the past decade, the company has systematically leased out small parcels of agricultural land (around two to six hectares in size) across Ukraine, aggregating these into large-scale farms that now operate industrially. According to NCH Capital’s General Partner, George Rohr, the leases give the company the right to buy the currently-leased farmland once the moratorium on the sale of land in Ukraine is lifted.

Another subset of companies have Ukrainian leadership, often a mix of domestic and foreign investment, and may be incorporated in tax havens like Cyprus, Austria, and Luxembourg. Some of them are also led by Ukrainian oligarchs. For instance, UkrLandFarming controls the country's largest land-bank, totalling 654,000 ha of land. 95 percent of the shares of UkrLandFarming are owned by multi-millionaire Oleg Bakhmatyuk with the remaining five percent having been recently sold to Cargill. Similarly, Yuriy Kosiuk, Ukraine's fifth richest man, is the CEO of MHP, one of the country's largest agricultural companies, which holds over 360,000 ha of farmland.

With the onset of the political crisis, several of these mostly Ukrainian-based companies have descended into crisis themselves. One example is Cyprus-incorporated Mriya Agro Holding, which holds a land-bank of close to 300,000 ha. In 2014, the company’s website (which is no longer available online) indicated that 80 percent of the shares of Mriya Agro Holding are/were owned by the Guta family (Ukrainian), who hold primary leadership positions in the company. The remaining 20 percent are/were listed on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange.

According to news sources, in summer 2014 the company defaulted on its payments for two large Eurobonds, putting its future into question. The company first enlisted the support of US-based Blackstone Group and Ukrainian-based Dragon Capital, both of whom withdrew support after only one month; and later, the international auditing and financial service firm, Deloitte. An international bondholder committee was struck, comprised of several US and UK-based investment groups (including CarVal Investors – Cargill’s investment arm), which together own over 50 percent of the debt owed on Mriya’s 2018 Eurobonds and 15 percent of the 2016 Eurobonds. The future of this firm is unclear with some sources suggesting a risk of bankruptcy.

Other Ukrainian-owned companies incorporated in tax havens are also experiencing difficulties. Sintal Agriculture Public Ltd (based in Cyprus, traded on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange as of 2008, and holding almost 150,000 ha of land) ceased trading in shares on January 29, 2014 "until further notice" after bankruptcy proceedings were initiated against the company. In 2013, its website (now also defunct) indicated that 36.3 percent of the company was free floating shares.

The potential bankruptcy of these corporations, and the involvement of Western investors in the crisis management, raises questions about the fate of the agricultural land they hold. At this time, it is not clear how control over the agricultural lands in question will be addressed and what the role of foreign companies and funds who have invested in these companies will be. However, if things progress in a similar way to neighboring Romania, foreign control of this land could transpire.

Romania has a similar story of dissolving collectivized farms, giving land titles to collective farm workers, and imposing a moratorium on the sale of agricultural land. Loopholes in the country’s national legislation have created opportunities for foreign control of land via bankruptcy proceedings. As documented by Judith Bouniol, the bankruptcy of national agribusinesses has provided a gateway for foreign control of Romania’s farmland.

It is far from clear if the same scenario could take place in Ukraine. However, this lesson from Romania emphasizes the importance of keeping close watch on these agricultural land deals. In addition, the murky situation around land ownership in Ukraine raises many questions. Perhaps the most important is whether the growing concentration of Ukrainian land in the hands of a few oligarchs and foreign corporations can benefit the country, its people, and its economy.

--

1 Two land investment databases were accessed over the past year: the Land Matrix accessed in July 2014 and April 2015, and GRAIN’s 2012 data set on land investments worldwide. Taken individually, these databases suggest foreign land acquisitions of between 997,000 ha to 1.7M ha. When consolidated, individual deals reported by these databases represent over 2.2M ha of land in Ukraine.

See Article - http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/who-owns-agricultural-land-ukraine

Article from -

The Oakland Institute, P.O. Box 18978, Oakland, CA 94619 - 510-474-5251

info@oaklandinstitute.org

Shafted: The winners and losers of Ukraine’s austerity agenda

By:

Elizabeth Fraser

On March 2, 2015, the Ukrainian government passed amendments to its 2015 budget that will cripple the economic well being of most Ukrainians, but satisfy the International Monetary Fund (IMF). At the cost of their pensions, tax increases, sky-rocketing energy bills, and a re-organized banking sector, Ukrainians are now poised to get an IMF-led bailout of up to $40 billion. These austerity measures will have a huge adverse impact – with inflation soaring, many citizens of Ukraine already face dwindling financial reserves. Increases in taxes, energy bills, and lost pensions, are enough to throw any family into financial turmoil. These reforms also have vast implications for Ukraine’s agricultural sector.

The IMF and World Bank have been pushing for Ukraine to lift its moratorium on the sale of farmland for some time. In early March, Heinz Strubenhoff, the agribusiness investment manager for the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation in Ukraine, told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that “it’s time to think about privatization,” and urged Ukrainians to “prepare everything to allow for farm land sales (to foreign and domestic investors).” Given the power that the IMF and World Bank hold over Ukraine right now, their wishes may finally come true.

Land is a precious commodity in Ukraine. The country is known as Europe’s bread basket, and holds some of the world’s most fertile soils. In 2001, Ukraine passed a Land Code, providing Ukrainians who had previously been part of collectivized farms with titles to approximately four hectares of land each. Since then, the majority of farmland has been in the hands of either smallholder farmers or the government, with a country-wide moratorium on its sale.

See rest of the article -

http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/shafted-winners-and-losers-ukraine%E2%80%99s-austerity-agenda

NEW !SEE: TRAVELING IN SOUTH AFRICA - MOZAMBIQUE - ZAMBIA - TUNISIA - COPTIC EGYPT - MOROCCO - under CELEBRATE HUMANITY - SEE: - CURRENT Africa 2020

Embrace Foundation

- Great Visions TV

- Inspirations

- Media

- Possibilities

- Astrophysics, Quantum Physics & The Nature of Reality

- Deconstructing Nuclear Fission & Nuclear Waste

- Defense Industry as Community Builders

- Defense Industry As Energy Providers

- Global Water Shortages

- Innovative Technology

- Intelligent Communities & Development

- Pentagon & Non-Western Nations

- Recreating

- Resource Based Population

- Sharing Community Resources

- Protecting Human Rights

- Spiritual Ecology

- Syria

- Write to Us

Embrace Foundation Retreat Center

Embrace.Foundation (skype messaging) - 011+1+212.675.4500 (New York)

Click to Email Us